The Steelers have some of the most notorious rivalries in the NFL. Their games against the Browns are always intense. Their rivalry with the Ravens is equally fierce as some fans consider them Old Cleveland. Then there are the Bengals. The rivalry with the Oilers had its own specific intensity in the old AFC Central, as did the one with Jacksonville during their short tenure in the AFC Central.

The Steelers, however, have a unique and significant rivalry with the Oakland Raiders. While it may not be as intense as it was in the '70s, it holds a special place in NFL history. The rivalry reached its peak in 1977, a moment that stands out for its unusual nature. It was a time when the rivalry transcended the football field and found its way into a court of law, a testament to its historical significance.

In 1977, George Atkinson filed a defamation lawsuit against Steelers head coach Chuck Noll following the comments Noll made following the 1976 season opener against the Raiders. Atkinson had blindsided Lynn Swann with a hit to the neck and head just before halftime. In his press conference the following day, Noll stated: "There is a certain criminal element in every aspect of society. Apparently, we have it in the NFL, too."

Perhaps Noll might not have commented, but this wasn't the first time Atkinson had gone after Swann. In the 1975 AFC championship game, Atkinson hit Swann in the back of his head with a forearm, giving him a concussion. Then we have the actions in the 1976 game, egregious enough for announcer Don Merideth to note that the hit was unwarranted.

The result of Noll's harsh words is that Atkinson filed a libel lawsuit against Chuck Noll, the Steelers, and Oakland Tribune columnist Ed Leavitt who had written Atkinson could have killed Swann instead of giving him a concussion and that he could have been facing a murder rap.

Ironically, the lawsuit also prompted the Steeler's Mel Blount to file a lawsuit against Chuck Noll for what Atkinson's lawyer got Noll to admit on the stand. Furthermore, Lynn Swann had considered suing Atkinson, though they never did.

That Atkinson Lawsuit

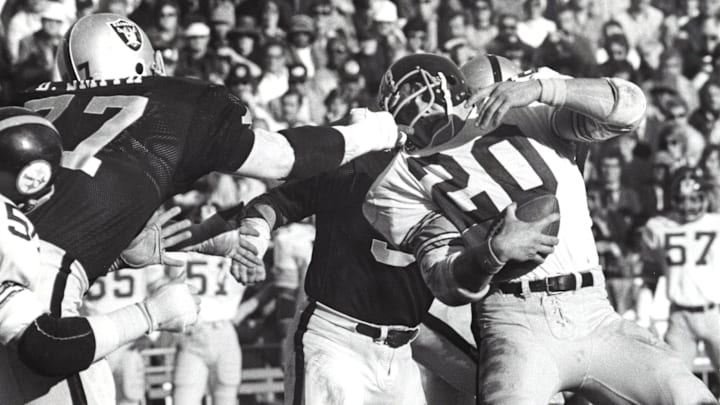

Any time the Raiders played the Steelers in the 1970s, they didn't play football as much as they waged a war. The Raiders players, coach John Madden, and owner Al Davis have never gotten over the immaculate reception that caused them to lose their playoff game in 1972. The Raiders would beat the Steelers in the 1973 divisional round of playoffs only to lose to the Dolphins. Then, the Steelers beat them in the 1974 and 1975 AFC Championship games. The Raiders only got over the hump to the Superbowl to win a title in 1976.

The Steelers' success over the Raiders in the playoffs left a bitter taste for the Raiders, leading to a palpable hostility on the field. The 1974 regular season game, in particular, saw the Raiders roughing up Steelers quarterback Joe Gilliam, a game that some claim may have hastened Gilliam's spiral into substance abuse. The Steelers, on the other hand, had built their team to mirror the Raiders, a strategy that paid off in their victories.

Given their animosity on the field, it's not surprising this sort of thing happened. It put Chuck Noll in a precarious position as well. In the opening arguments, Noll's Lawyer, James Martin MacInnes, who formally represented Patty Hearst, stated, "Mr. Atkinson may be a charming young man you may safely invite him….to your home. But you may not, with equal safety, encounter him past the line of scrimmage on a football field, particularly if your name is Lynn Swann and your back is turned."

Atkinson's lawyer, future San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown, opened with, "This is opening pro football's Watergate. Pro Football is on trial here. If the jury rules Atkinson is not slandered….then the term' criminal element' has been judicially certified as a viable, proper, accurate definition of the game….[expletive], you could bring a class action suit against showing the 'criminal violence of football on TV…" Willie Brown may have had a point, but a weak one, given such violence, helped increase the popularity amongst fans.

On the Stand, Atkinson did his best to defend himself: "…to be called an Assassin [Jack Tatum] or the Enforcer someone that plays with the intent to maim-because of one play, one incident in the nine years I played football, I'm labeled for the rest of my life, you know." Perhaps Atkinson never received that label. However, his teammate Jack Tatum did, if only for his pre-season hit on wide receiver Darryl Stingley, leaving him paralyzed.

When NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle and Raiders owner Al Davis took the stand, it highlighted that the feud between the Raiders and Steelers was secondary to the feud between Davis and Rozelle. In part, the feud was fueled by Davis feeling Rozelle got all the credit for the AFL-NFL merger, but he never received credit for his efforts to make the merger happen. Also, because of the Atkinson lawsuit and, later on, Pete Rozelle's attempt to block the Raiders' move to Los Angeles.

At the height of the trial, Noll took the stand, and Brown confronted Noll with NFL footage from the Steelers, in particular, and Brown asked Noll if some of his players could be considered part of the criminal element. The questioning forced Noll to admit that "Mean" Joe Greene, Ernie Holmes, Mel Blount, and Glenn Edwards could also be considered part of the criminal element in the NFL. It's somewhat ironic Jack Lambert did not make that list. Yet the real irony is that it forced Mel Blount to file a lawsuit of his own against Chuck Noll for his on-the-stand comments; however, that went away after he signed a new contract with the Steelers.

Despite Noll's admissions, the jury ultimately sided with him, and Atkinson did not receive a damage award. This decision was seen as a victory for the NFL, with other owners celebrating what they believed was an attempt by Davis to assault the league with the lawsuit. However, the trial was not without its consequences, with Dan Rooney calling it 'depressing and ugly ', fearing it could tarnish the NFL's image for years to come.

Was there a criminal element in the NFL?

This is a subjective question. Steelers fans who lived in that era will swear the Raiders were dirty. Raiders fans would swear the Steelers were dirty. Then, some might question some other players around the NFL. You had Fred "The Hammer" Williamson, whose trademark play was a leap and dive into a player with his shoulder pad and was eventually outlawed.

Hardy Brown, a player for the 49ers in the 50s, might still hold the NFL record in a career for causing the most knockouts on the field. Even Steelers legend Ernie Stautner was rumored to have soaked his arm wraps hardening them to bruilize opponents. The NFL, between the 50s through the 80s, had many hard hitters until the NFL started penalizing that type of play on the field.

In an interview, John Madden once said, " And when they wanna say the Raiders are dirty. yeah, yeah, we're dirty, yeah, so what are you going to do about it?" While his comment was tongue in cheek, the NFL as a league didn't do anything about it. However, Chuck Noll and the Steelers did. Noll knew the type of players the Raiders had, and in building his team, he found his own tough guys who would not back down from the Raiders' aggressive defensive style.

Hence, you had Mean Joe Green. People didn't call him mean for nothing. Joe Green once spit in the face of Dick Butkus, who declined to challenge Greene and walked away. Ernie Holmes is a hard hitter. His teammate Mike Wagner once said he thought Holmes wanted to beat opposing players to death on the field but within the confines of the rules. He would do it fair and square in with what the NFL allowed him to do.

With Blount, perhaps he did get away with a few things here and there, but most of his hits were within the confines of the game's rules... Remember that in 1978, the NFL changed the passing rules to neutralize Blount theoretically, but it did not help. Glenn Edwards put the hurt on a few players, too. Aside from those accused of a 'criminal element' in court Dwight White used a vicious headslap, and Jack Lambert just hated anyone in an opposing uniform. Look at what he did to Cliff Harris in Super Bowl X.

If any Steelers players represented a 'criminal element,' what about the Raiders? In the 60s, you had Ben Davidson, a player many called the dirtiest player ever. Then heading into the 70s, you had George Atkinson and Jack Tatum, who people began labeling as the dirtiest ever. Raiders' long-time center Jim Otto said this was football and Swann should have never cried the way he did. Atkinson said in later interviews that football isn't a contact sport; it's a collision sport. He later called Swann soft. Well, that was a message picked up on by other Raiders defensive players of that era: Phil Villapiano, Ted Hendricks, Skip Thomas, Willie Brown, Lester Hayes, or any other Raiders player from that era.

Chuck Noll made one distinction during the trial: the Steelers would hit their opponents head-on but were not going to flaunt the rules of the game. He felt Atkinson did just that. You can see the hits he made on Swann here and draw your own conclusions as to whether Atkinson's lawsuit had any merit. Was there a criminal element involved? Well, if you view it through the NFL Rules of 2024, then yes. However, in the NFL in the 50s, 60s, and 70s, defensive players had more leeway in what was considered legal.

So, in reality, while there was a nasty element to the game, each team wanted to be tougher than the team they faced. Yes, some hits were nasty, yet legal. A few hits may have crossed the line, but each side knew it would happen. Each side pounded quarterbacks hard. Defensive backs sent a message to wide receivers: do not cross the middle. You will pay the price.

While Atkinson claims Swann's life was never in danger, given what we have learned about concussions in the NFL, that was not entirely true. In the end, calling their actions 'criminal' was a bit of an overstatement. If anyone could characterize an event as potentially criminal, you would need to re-visit the Cleveland Steelers game late in 2019 when Myles Garrett hit Mason Rudolph with his own helmet. Even then, most eventually backed off calling that criminal as well.

To sum the matter up, look at Joe Greens' feelings on the matter. He felt the lawsuit victimized Noll for his success. Greene felt the Steelers and Raiders should have settled the Atkinson lawsuit on the football field, not in a courtroom. Perhaps he was right; that would have been a game for the ages in the Steelers-Raiders rivalry.